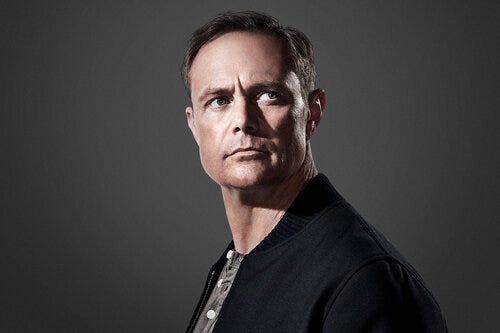

Sophie Toscan du Plantier: What Would Paul Holes Have Done?

I'm an affirmed fan of Paul Holes. If he had been in West Cork in 1996, could the case have been solved there and then?

I returned to true crime after watching I’ll Be Gone In The Dark, a series about Michelle McNamara’s hunt for the Golden State Killer. A star of that show was a man called Paul Holes. Paul is a lovely name, but more than that, Paul Holes is a knowledgeable scenes of crime expert going back decades. If you’re interested, and I can strongly recommend it, he has a short podcast show on Audible about a case early in his career, when he was a junior analyst. It is about the murder of Emmon Bodfish. He talks in detail about his approach to that crime scene. Bodfish had been dead for days, or longer, when the body was discovered, as evidenced by the flies and maggots slowly eating his flesh. Yes, this show has detail. The kind of detail I really don’t like listening to, never mind watching on television. But it gave me a new idea.

Bodfish died in 1999, just three years after the 1996 murder in West Cork of Sophie Toscan du Plantier. Back then, using DNA to catch criminals was in its infancy, quite basic, and not well understood by police. I don’t think Paul Holes refers to DNA at all in the Bodfish case. But he does have a deeply thorough, perhaps a little obsessive, approach to the scene of a crime that he lays out in detail.

Bodfish was found indoors, in a hot room, and had been there undiscovered for many days. Sophie was found outdoors in winter, just a few hours after her death. In the Sophie case, the pathologist was delayed for several reasons. He had celebrated his birthday when he took the call quite late on the Monday afternoon or evening and he had a long drive of several hours. He set off on the Tuesday morning and arrived on Tuesday afternoon, making it around 36 hours after the murder. He was heavily criticised for this but it was not unusual.

The police on the scene were nervous about leaving the body outside in the lane for a second night. They believed it was more respectful to take Sophie to the mortuary that night, before the pathologist arrived. A phone call to the pathologist confirmed that he agreed with this course of action as the body would be so cold as to make an accurate time of death assessment impossible. There seemed to be two topics of interest here: (1) gauging time of death from body heat and (2) respect for the victim and her family.

I don’t recall anyone suggesting that the body should remain in the lane to allow detailed forensic analysis. Even without DNA, it turns out there was a lot you could do in 1996 to assess the scene. The reason Sophie was left in place in the end was that the local police overruled the outside experts and insisted on the body remaining in place so that the pathologist could see the setting.

Paul Holes talks of his detailed crime scene approach, his caution and thoroughness in great detail in several of his shows. In the Bodfish case, he removes the clothes at the crime scene and begins an initial inspection of the body. He explains that if you put the body in the bag fully clothed, blood patterns and colouration can change. He needs to separate them out and do an initial analysis in situ. He explains that you can sometimes tell the sequence of injuries, or blows, and start to understand the attack, just from careful inspection of the scene.

Holes further explains that he has a deep trust in a topic he calls victimology. He wants to understand as much about the personality and life of the victim as he can. Most true crime shows are gruesome investigations about the police procedure and the hunt for the killer, with just a couple of minutes at the beginning about the victim and who they were, and their state of mind at the end of their life.

Taking the Paul Holes approach, trained in the USA, at exactly the same timeframe as Sophie was murdered in Ireland, you can see that possibly a different outcome could have been achieved.

Was anything missed at the Sophie crime scene? Even the highly edited footage and stills shown in Murder at the Cottage demonstrate that the photographer did an excellent job. I know from reading books that the full set of photographs left nothing at all to the imagination, from any angle, and I am relieved not to have been exposed to those shots.

But the detailed photos were done in the morgue. Yes, there are photos from the crime scene, and very specific details were noted. One detail that appalled me and lingers is the observation that Sophie’s head had made an impression in the hard ground, due to it being struck with such high force. I shudder, and continue.

Yes, the pathologist was slow off the mark. But in West Cork, at Christmas 1996, facing the only murder they had ever seen, the local police could not have been as thorough as Paul Holes, an American scientist who started his career in 1994, and familiar with murder in the east bay of San Francisco.

Paul Holes examined the entire house of Bodfish in great detail, noting that someone had ransacked a chest of drawers, but missing the same in the bathroom. He had never seen a floor safe before and mistook it for part of the toilet plumbing. Nobody is perfect.

Back in West Cork, we are shown photos of Sophie’s house. We see a rub of blood on the outside door handle, two wine glasses, her coat, and a number of items which have become part of her legend. But the briars in the lower pasture, believed to be the route that Sophie and her assailant took in the early hours of 23rd December, were roughly hacked away. Today, every strand of briar would be searched for blood and DNA samples, but not then.

The gate had blood smears on it too, and was lost in an evidence warehouse soon after. There were no fingerprints on the gate. There were no prints on the stone or the concrete block that were found covered in blood. In 1996 the focus was on fingerprints to track the presence of a suspect, whereas now even DNA sounds like old technology.

Putting all of this information together, it seems likely that indicators at Sophie’s crime scene were missed. The Irish police had many advantages that were not available at the Bodfish crime scene. They arrived within hours of the murder. A local pathologist might have been able to gauge time of death from the body at that point, but this had been a cold night. It was likely already stone cold. Did they tip toe around the large garden with its cottage, the lane, and the environment around it, with the thorough experience of Paul Holes? Certainly not. They didn’t have the experience.

But there is one tactic which Holes places high value on that was not only possible in 1996, but crucially, remains possible today for any cold case. Victimology. By learning more about the victim, we learn more about a list of possible suspects, and we get closer to the truth. After 20 years, many books, articles, news reports and TV shows, witnesses have started dying of old age. We cannot learn anything more about the events of the night of the 22nd December 1996. But we can learn more about Sophie. There might be a secret or two there, still. It is time to watch the Netflix series, the one supported by her family, which is said to focus more on her life and times.